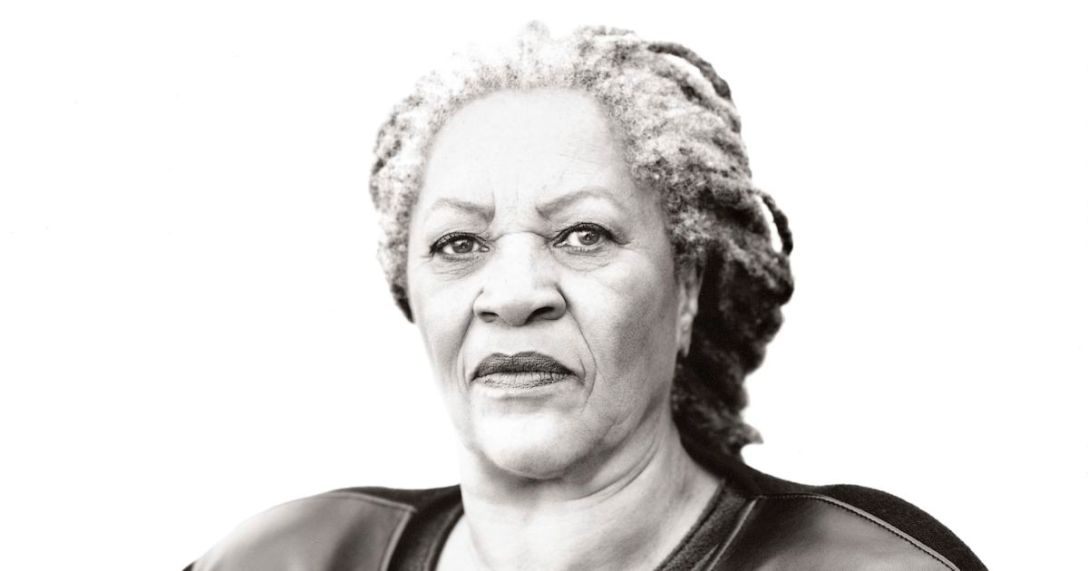

Toni Morrison – The Imaginarium

Born: Feb 18, 1931

Most known for: Beloved, Jazz, The Bluest Eye

The characters were ready. Full and alive. The writer in the house knew it and so would the readers in time. For months the writer met the characters where they stood, noticed their hair, the way they breathe, how they may flick a cigarette after a long drag, each unmistakably human in their own way, and told their story. They began as an idea, perhaps even a boring idea, then grew into a question Toni Morrison didn’t know the answer to. She didn’t wait to learn more. No. Any character who had “too little imaginative space there for [her] purposes” she would invent their thoughts, “plumb them for a subtext that was historically true in essence, but not strictly factual.” Toni met her characters where they stood, or sat, having recently emerged from a river. She would not flee no matter what was for her a question which refused to resolve or the emergence of terrain formidable or pathless. This was part of her process—her habit. Morrison brings readers into her imagination. Her intention, she writes, is

to invite readers (and myself) into the repellant landscape (hidden, but not completely; deliberately buried, but not forgotten) was to pitch a tent in a cemetery inhabited by highly vocal ghosts.

Toni didn’t even raise her head. At first. From her bed she heard the characters move around but that wasn’t the reason she lay still. It was a wonder to her that her characters had realized that every house wasn’t the same, that hers was welcoming. Suspended between sleep and fear of frightening them away, Toni crept from her bed in the darkness to begin to write. She was interested in the questions they sought, in the characters’ interest in living life or leaving it. Their past became her present and she wrote before the light came. When she didn’t contact her characters she watched them, dreamed them back from forgetfulness. She observed their shadows, using her energy to imagine them whole. She pondered them into full color. This was her process for contact. To imagine the characters as more than what the page demanded of their outrageous behavior. As she explains,

Writers all devise ways to approach that place where they expect to make the contact, where they become the conduit, or where they engage in this mysterious process. For me, light is the signal in the transition. It’s not being in the light, it’s being there before it arrives. It enables me, in some sense.

There, in the darkness, she wrote her characters alive before her sons would wake up and begin their demands upon her attention. Becoming a habit borne of necessity, she learned how to work very carefully with what was between the words. What the characters did not say. Her brain was devious. In the hours before the light opened and rolled the real world out before her in shameless beauty. It never looked as terrible as it could be and it made her wonder what other secrets it held—what other ideas which became questions which became characters which became stories penned in the early light. By noon she would finish writing and not writing, which, Morrison claims, is what “gives what you do its power.”

Not quite in a hurry, but losing no time, Morrison shows how writing when possible becomes writing whenever possible, even when that writing is just imagining her characters robustly alive, standing before her or waiting by her desk before dawn. Her necessity became her habit. Her habit became her novels, following the characters she had seen. All from a single moment of knowing they were real. As she describes writing Beloved,

I husband that moment on the pier, the deceptive river, the instant awareness of possibility, the loud heart kicking, the solitude, the danger. And the girl with the nice hat. Then the focus.

The focus after the vision. If Morrison teaches us one thing from her process, it is this: See clearly. Imagine the characters fully. Really inspect them. Know them beyond the page. Then write—every morning. Write until the light finds you. Write until your words glow, or step from a river fully formed after years of haunting, wearing a beautiful hat.

…

See also Jack Kerouac’s advice on writing as told in his voice.

If you enjoyed this, subscribe here for further articles in this series and the industry’s best writing tips.

Stylistic structure taken from the first few pages of Morrison’s Beloved.

References:

Schappell, Eliza. “Toni Morrison, The Art of Fiction No. 134,” Paris Review, Fall 1993, accessed online at https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/1888/toni-morrison-the-art-of-fiction-no-134-toni-morrison

Morrison, Toni. Beloved. Vintage, 2004, p. xv – xix.